03 Jul Full Duty with Great Credit: The 16th Michigan on July 2nd, 1863 – Part 2

by Jared Mike

Lt Col Norval Welch had an excellent leadership record in a number of bloody battles and minor skirmishes. Gettysburg was his first major battle in which he would be the official commanding officer of the regiment. I previously posted about the lead up to Gettysburg for Welch and the 16th MI. I also led you into their first position during the opening of the fight for Little Round Top. Now let us go to part 2 and close the story on this regiment.

After being placed on the left of the 20th ME during their initial deployment, Welch sent forth his two largest companies onto the skirmish line. Within minutes, he would be shifted to the right as the Confederates launched assaults east of Devil’s Den toward Little Round Top. The 44th NY and 83rd PA skirmishers would be driven from the woods on the north side and saddle of Big Round Top as the 16th MI got to their assigned area. Moving to the right of the 44th NY, the 170-odd Wolverines could not form a proper linear formation due to the rocks and boulders on a shelf (or flatten part of a hill). Instead, the men used whatever protection they could find as the enemy was closing in rapidly.

Charging at them would be the 4th TX and part of the 5th TX, making their way up the hill. Using more or less “modern tactics”, squads of men would provide cover fire as others slowly inched toward the Wolverines. Twice the Texans were repulsed but not totally driven off of Little Round Top, with men also using the rocks and folds in the ground to protect themselves. Casualties were heavier in the Texans’ ranks but the smaller Federal regiment was also taking losses. Private Jacob Genner was hit in the chest and will lose his life on July 10th, away from friends and family. Color Sgt Eldridge Potter was hit in the leg and Color Corporal Henry Welbon was wounded in the arm; a few casualties in the vulnerable color guard. Officer casualties were heavy too as Capt. Benjamin Franklin Partridge (Company C), 1st Lt Martin Borgman (F) and 1st Lt Wallace Jewett (K) plus others went down killed or wounded.

To make matters worse, the Union defense in Devil’s Den collapsed; releasing Confederate reinforcements to aid the Texan assault. Elements of the 48th AL and 44th AL swung toward the open right flank of the 16th MI, creating a serious issue. Welch would later write in his report: “We remained in this position for half an hour, when someone (suppose to be General Weed or Major-General Sykes) called from the extreme crest of the hill to fall back nearer the top, where a much less exposed line could be taken up. From some misconstruction of orders, and entirely unwarrantable assumption of authority, Lt Kydd ordered the colors back”. Unfortunately, Welch cracked (some form of PTSD) and probably ordered the colors back himself. Soon the right flank started to go with the colors and so did Welch! The situation was so desperate that Col Vincent jumped onto a large rock and supposedly yelled “Don’t give an inch! Don’t give an inch!”. He probably yelled something more profane and used the riding crop in his hand on the men. A bullet slammed into his groin, mortally wounding Welch’s friend.

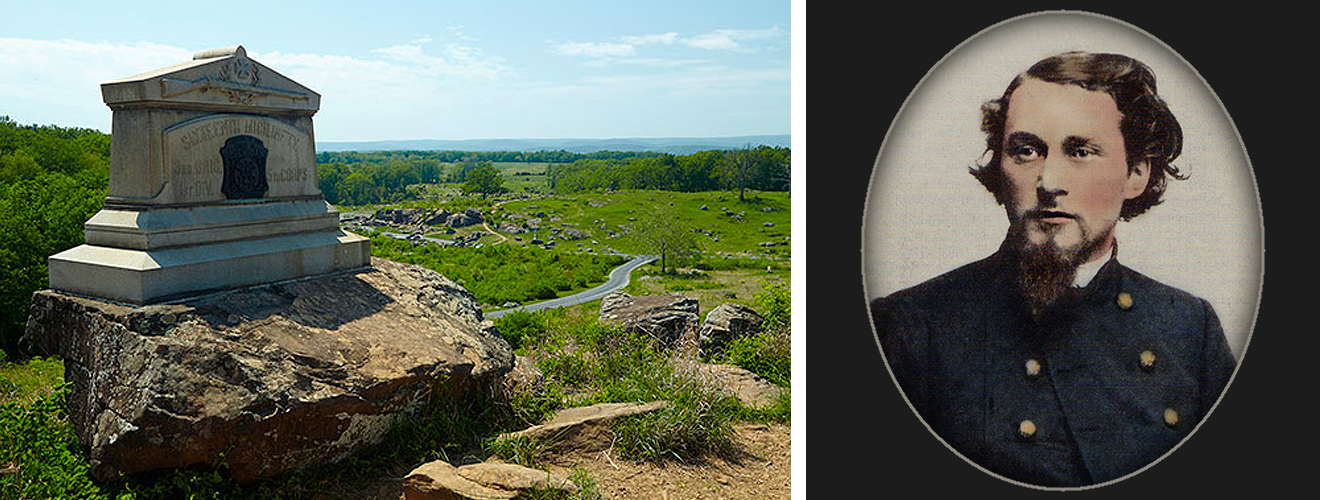

The collapse of the right flank of the 16th MI now allowed the Alabamians and some Texans to shoot into the center and left of the 16th from the side and rear. The 44th NY also experienced fire in their rear, making the situation dire. Companies A and G of the 140th NY now charged down Little Round Top’s summit with an officer leading them. An Alabamian opened fire, killing Col Patrick O’Rorke with a single bullet to the head. His men opened fire on the soldier, putting supposedly 17 bullets in him. The New Yorkers now placed themselves on the right of the Wolverines, near where the 16th MI monument now resides. The rest of the 140th NY formed up and stabilized the line.

The 16th MI now had less than 70 men in the ranks as nearly 50 men fell plus another 50 (and their commanding officer) were out of the ranks. The various regiments on the hill fortified themselves that evening as the enemy took potshots at them from Devil’s Den. On July 3rd, the brigade was ordered off Little Round Top but the 16th MI refused. The men felt they fought well and the flag should have stayed with them. If the flag was returned then they would leave. Col James Rice, now Brigade Commander, understood and sent someone to find the flag. Somehow the flag was found and the party (including Welch) joined the rest of the men. The regiment now left Little Round Top and moved toward the woods north of Munshower Hill. The regiment suffered 72 casualties out of roughly 250 men during the battle.

The regiment joined the pursuit of the Confederates but Welch was not his normal self (with the PTSD taking hold of him). He would leave the regiment on July 17th and returned briefly in the winter. He was never the same man as before, avoiding his regiment as much as possible. He would miss the bloodletting of the Overland Campaign, angering the men with that decision. Major Robert Elliott would die in late May leading his men, being reaped praise that was similar to Welch two years prior. Welch would return in the late summer to the regiment, the troops no longer having the same respect he had once earned. Now a Colonel, Welch led his men at Peebles Farm (Sept 30th 1864) from the front. Jumping over the breastworks and into the Confederate lines, he would instantly die. A tragic end for a man who had the highest of highs and the lowest of lows. The regiment would muster out under Partridge in July 1865, a regiment that suffered horrible losses in the war.

Oliver Willcox Norton would write a history about the action that took place on Little Round Top in 1913. While his description of the battle is relatively accurate, he ignores facts when talking about the 16th MI. As a bugler and headquarters flag bearer for the brigade, Norton was close to Vincent. In fact, he held him in high regard and was heartbroken by his death. Looking at the reason why, he saw that Vincent moved to halt the partial withdrawal of the 16th MI. Therefore, it seems that he put the blame on Welch and therefore would criticize his performance that day. While I used some quotes of his in my titles, this was not what he said about Welch or part of the regiment on July 2nd. Norton’s clouded viewpoint shaped our perception of the regiment at the bloodiest battle in North America. Gettysburg was not their best day but the men fought hard but seemed to not get the credit they deserve.

Viewpoint from the center of Lt Col Norval Welch’s 16th Michigan on Little Round Top. (Author’s Photo)

Bibliography for Parts 1 and 2:

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901

Busey, Travis W. and Busey, John W. Union Casualties at Gettysburg: Comprehensive Record Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishing, 2011

Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987

Priest, John Michael “Stand to It and Give Them Hell”: Gettysburg as the soldiers experienced it from Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top, July 2nd, 1863 California: Savas Beatie, 2014

Crawford, Kim. The 16th Michigan Infantry in the Civil War: Revised and Updated East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 209

Norton, Oliver Willcox. The Attack and Defense of Little Round Top: Gettysburg, July 2nd 1863 Gettysburg: Stan Clark Military Books, 1913

No Comments